When we think of memorable silent film comedians our thoughts go to Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, Langdon, – and Arliss. Who? Well then, this is still one of the better kept secrets of film history and it’s high time we put a spotlight on it. In recent years, the comedies of Raymond Griffith, Reginald Denny, and Douglas McLean have returned to circulation after 90+ years absence from the screen, and of course they were never part of home video. And these rediscoveries have proven quite enjoyable. We also realized what we were missing all this time. My purpose here is to add George Arliss, actor, author, playwright, and filmmaker, to this growing list of rediscovered film comedians.

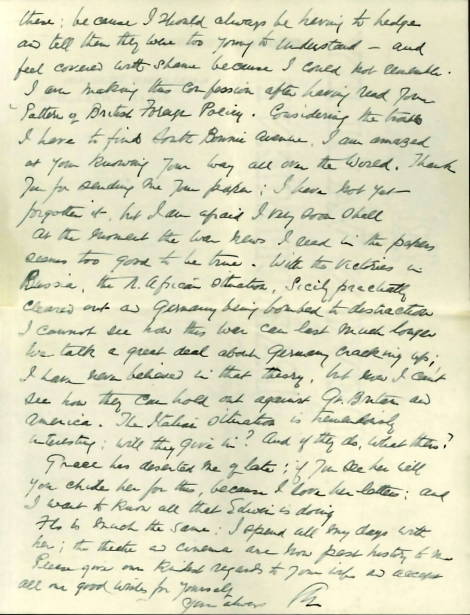

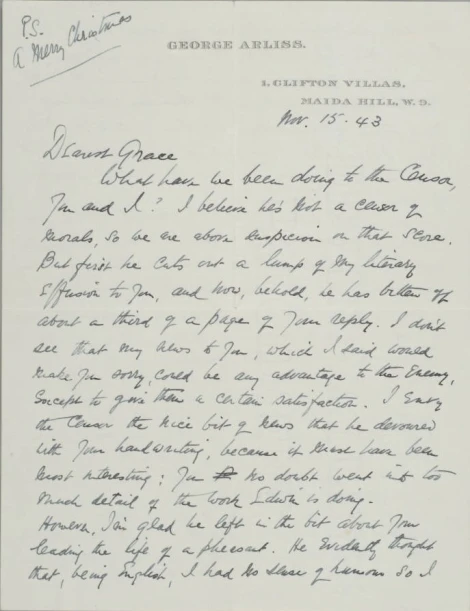

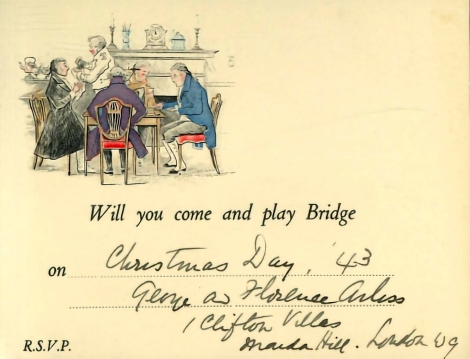

Having published six books on Mr. A (as I call him) since 2004, I am more or less regarded as his official biographer. Not that this effort was a chore. It was and still is a delightful journey of discovery. He was known as one of the great dramatic actors of his era and racked up popular and critical successes in all the media of his time from the stage, silent films, sound films, even radio. Mr. A was also known as an authentic gentleman and a most kind one at that. I tried to dig up “dirt” on the man but I couldn’t even find unsubstantiated rumors.

An early experience in mass media occurred with his broadcasting in 1922(!) and was not what we would expect of a fellow who spent 32 years of his life in the Victorian Era of the 19th century. Arliss devoted that first broadcast to denouncing censorship in films. This was before Will H. Hays was hired by the studios to be their moral watchdog.

The Arliss Comedy Plays

Arliss began his career primarily in drama and in his early career he played in support of two pillars of theatre: Mrs. Patrick Campbell and Mrs. Minnie Maddern Fiske. But there was always a second string to the Arliss bow: his comedy plays and later his films. George Arliss’s roots in comedy were long and deep even before he made films. His first brush with comedy was not as an actor, but as a playwright. He wrote a three-act farce called THE WILD RABBIT in 1898. I thought the title was takeoff on Ibsen’s THE WILD DUCK but apparently there was no tie in. The plot involves a case of mistaken identity between a nobleman and his hairdresser. The latter is lavishly treated like, well, a nobleman by the ladies, while the former is bashed about as the tradesman he isn’t.

Following an out-of-town tryout in Wolverhampton (UK) in January 1899, THE WILD RABBITT opened at the Criterion Theatre in London in July. One critic was not amused but admitted that “the simple minded playgoer roared with laughter.” Mr. A’s first effort at comedy closed after three weeks but not because of a lack of public support. It was a very hot summer and air-conditioning hadn’t been invented yet. With temperatures in the 80s the last place the public wanted to spend two hours was in a stifling theatre.

In 1903 Mr. A wrote another comedy, THERE AND BACK, the plot of which sounds a lot like the Laurel and Hardy film, SONS OF THE DESERT, made thirty years later in 1934. The Arliss story was a variation of a staple of French farce. Two wives want to get away for a holiday without their husbands so they make up a story about going to visit a sick friend. The husbands are a bit suspicious but accept the explanation. While the wives are away the husbands run into their “sick” friend who is fine and has not seen the wives lately. Like Ricky Ricardo would say, the wives have a lot of “s’plainin” to do.

Mr. A did not appear in THERE AND BACK but his wife Florence did. The play was a hit on Broadway and Charles Evans, who played the lead as one of the husbands, would tour in it for many years. Arliss regarded Evans as his “good luck charm” and found parts for him later in his Hollywood films. But the theatre world was not finished with THERE AND BACK. It was adapted into a musical called I LOVED A LASSIE and went on to even greater popularity in the UK.

As an actor, Arliss managed to work his way up from playing in the provinces (i.e., the sticks) and arrived at the West End (the London equivalent of Broadway) by 1900. In 1901 he accepted an offer from Mrs. Patrick Campbell’s troupe to play a season in America although he was limited to supporting roles. The tour was a success and when the Campbell troupe returned to Britain, Mr. A decided to stay on for a bit in the states. His stay lasted for over 20 years. Ambitious for a starring role, he would eventually find his vehicle in a new play by Hungarian playwright Ferenc Molnar called THE DEVIL. This was a dramatic comedy that had been a smash hit in Budapest. Perhaps because the title suggested a warm climate, the play had its American debut on the sultry evening of August 18, 1908, at the Belasco Theatre. This opening night was jumping ahead of the traditional Broadway season by three weeks but there was a reason for this.

There was no reciprocal copyright law between the U.S. and Hungary at that time so anybody who could get their hands on a copy of the Molnar play could publicly produce it. And they did. Moving the opening night from September to August 18 seemed like a smart move until another DEVIL production followed. Playgoers were treated to two competing DEVILs that night and Broadway had never seen anything like it. The publicity helped both shows but the critics judged the Arliss version the better of the two. A New York Times reviewer proclaimed, “George Arliss at his best” and “Mr. Arliss’s performance is developed in the vein of brilliant comedy….” among other praises.

The Dramatic Comedy Films

THE DEVIL

Fast forward 12 years from 1908 and THE DEVIL is pressed into service again to become Mr. A’s very first film in 1921. Although he had evolved into a fine dramatic actor, it seemed that no role of his could completely escape the one-liner or the sarcastic deadpan reply. According to information in the AFI Catalogue, the film version of THE DEVIL was photographed at studios in Ft. Lee, NJ during the day while Arliss returned to the city to star in his latest hit play, THE GREEN GODDESS by William Archer, in the evening. The October 30, 1920 issue of Moving Picture World confirmed that filming had been underway for a month. The conclusion of filming was announced in the November 11, 1920 Wid’s Daily and the November 13, 1920 Moving Picture World. The sets included “a magnificent old-world ballroom” and “a reproduction of the Paris Art Salon.” Sculptor Frederick E. Triebel, a member of the Royal Academy, provided his artwork for free, according to Moving Picture World.

Editing and titling was finished by December 1920. George Arliss sat in on the assembling of the picture, as stated in a November 20, 1920 Motion Picture News brief. Mr. A had reportedly bonded with director James Young, the ex-husband of Clara Kimble Young, and they shared a ride to the studio each morning. Arliss also earned praise from cinematographer Harry A. Fischbeck, who was quoted in a February 5, 1921 Motion Picture News item, stating that the first-time film star “realized fully the importance of good photography and acted upon every suggestion. He made a camera-man feel like a most important personage.” Fischbeck also noted the difficulty of the shoot, specifically the constraints of shooting many interior scenes on “a four-walls-and-ceiling set.”

There were of course newspaper and magazine interviews regarding his film debut. Mr. A was well aware of the snobbery by actors from “the legitimate stage” who condescended to appear in movies. They liked the money but often took the opportunity of saying they had not seen their films and never would. Helen Hayes enjoyed a successful film career in the early 1930s, even winning an Academy Award. But she later admitted not having seen her films until they turned up on late night television decades later. This attitude was rather typical. An interviewer confronted Arliss with this mindset in the runup to the THE DEVIL’s premiere in January 1921. Asked “Do you take the screen seriously?” The actor deadpanned, “I do now that I’m on it.” The interviewer admitted to bursting out laughing at this reply.

THE DEVIL premiered at the Mark Strand Theatre on January 16, 1921, in New York City. The AFI Catalogue states that the film was a critical and commercial success, according to items in the February 5, 1921, February 12, 1921, and the February 16, 1921 Motion Picture News. The film set a record for Pathé, the distributor, for the “highest bookings in advance of release.” After successful pre-release runs at the Strand theaters in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Albany, NY; Shea’s Hippodrome in Buffalo, NY; and the Rialto Theatre in Lawrence, MA, the Mastbaum circuit of Pennsylvania and Gordon circuit of New England signed on to release the film. By that point the only question that filmmakers had for Mr. A was when could he be available to make his next film.

The comedy in the film, as in the play before it, generated from the fact that the audience knows that the kind philanthropist Dr. Muller is the Devil incarnate while the other characters are in ignorance. Viewers find themselves being pulled into the plot as a sort of “partner” with the devil as he lays his traps for the unsuspecting young lovers. In the play, Arliss spoke directly to the audience about his next steps to ensnare the innocents into eternal damnation. On the screen, Arliss communicates his schemes by writing in a gigantic diary that the viewer reads.

There are many sly touches throughout. For example, at a reception a group of important businessmen are only too eager to meet Dr. Muller. He plants seeds of jealousy in the characters’ minds by “assuring” them that their beloved could never be unfaithful – a thought that never occurred to the person until Muller brought it up! He manipulates them ever so subtly to arouse their jealousy, their anger, and perhaps violence.

Muller hosts a masquerade party at his mansion that shows every sign of turning into an orgy before the evening is over. There are indications of a censor’s scissors being used during some shots as scantily clad dancers seem to be enjoying themselves. It has been said that an unknown Frederic March is one of the partygoers but I found that impossible to determine.

The supporting cast performs well with future star Edmund Lowe as the artist/lover who can’t decide between his model or his best friend’s fiancé. Two up and coming actresses, Sylvia Breamer and Lucy Cotton, play these roles, respectively. Lucy’s aunt is played by Florence Arliss, George’s wife of 22 years then, who is billed simply as “Mrs. Arliss.” The opening credits do not acknowledge the Molnar play and the plot elements could be regarded as common story elements. The story is credited to Edmund Goulding who would become a major director within the next few years.

The fact that THE DEVIL exists at all today is a story in itself. A sole surviving 35mm print was found in the wilds of Saskatchewan, Canada, a number of years ago by Larry Smith, who is a Nitrate Film Specialist with the Library of Congress. Larry acquired this print and generously donated it to the LOC and then posted a video of it on Youtube. Eventually, I downloaded it and arranged to give it a 4k scan. Then a retired professional film editor, Lewis Schoenbrun, volunteered to further enhance the image quality. On January 16 of this year, we held an online “re-premiere” of THE DEVIL on the anniversary of its Centennial. Responses from friends have all been positive as Mr. A proves to be the master of droll humor in his very first film. I would very much like to screen this film before an audience someday.

DISRAELI

Now that the actor-playwright was “movie box office” he found himself with several offers for a second film. He preferred dealing with individuals rather than a big corporation, an experience he learned the hard way. In 1916, Arliss signed an agreement with director-producer Herbert Brenon to make what would have been his first film. But Brenon became seriously ill and the executives of Brenon’s company stepped in and cancelled the Arliss contract. Mr. A felt, not unreasonably, that he had been badly treated and sued the Brenon company in New York State court for breach of contract. He won his lawsuit at trial but lost on appeal. Brenon returned to good health but Arliss realized that the man did not have full authority to make contracts and chalked up the bad episode to a learning experience.

Selecting a second film after THE DEVIL’s success must have seemed like a no-brainer. By 1921, Mr. Arliss had long since established his stardom with one play that managed to run five years. The success of DISRAELI – called “the play with the funny name” – made the names of Benjamin Disraeli and George Arliss almost synonymous. The play was commissioned especially for Mr. A and was written by a well-known British playwright of the day, circa 1910, Louis Napoleon Parker. DISRAELI became Arliss’s most resounding hit up to that time and was all the more remarkable because of the esoteric story it told. The plot involved the great British prime minister’s effort to purchase the Suez Canal for Britain in 1874. Sounds exciting, doesn’t it? Well, not really. But by the sheer power of the Arliss wit, deadpan expressions, and his unique way with words, he starred in this play for five consecutive seasons, from 1911 to 1915, first on Broadway, then by traveling to every town and hamlet in the U.S. even if it was only for one performance. Arliss returned to Broadway with it for a 1917 revival.

Now in 1921, the play was everybody’s choice for the second Arliss film. This apparent “epilogue” for the play turned out to be more of a prologue. Mr. A would later film it for the talking screen in 1929 where he was honored with the Academy Award for Best Actor. The competition were no pushovers with Ronald Colman, Maurice Chevalier, Wallace Beery, and opera singer Lawrence Tibbett also nominated. Mr. A even faced competition from an unlikely source – himself. In a quirk of the Academy rules at that time, Mr. A was nominated for two films but won for only one, DISRAELI. Nobody ever repeated that sleight of hand again. He was also the first British actor to win the Best Actor Award.

I’ve held screenings of the ‘29 DISRAELI with college audiences and I can tell you that Arliss held them in the palm of his hand. When he was being dramatic, they were impressed. When he was being funny, they laughed. Perhaps it should not be surprising that when Arliss performed a one-hour radio broadcast of DISRAELI in 1938, over 50 million people worldwide listened in. After a successful theater career for over 40 years (he made his debut in 1887), the 1929 DISRAELI spearheaded a series of Arliss “biopics” on the screen with ALEXANDER HAMILTON (1931), VOLTAIRE (1933), THE HOUSE OF ROTHSCHILD (1934), THE IRON DUKE (1934), and CARDINAL RICHELIEU (1935). And he gave Bette Davis her first big break in films by casting her in his drama, THE MAN WHO PLAYED GOD (1932). She continued to publicly thank him right up to the end of her life.

Returning to 1921, early reports that DISRAELI would be Mr. A’s next film were confirmed in the May 2, 1921 issue of Wid’s Daily, and that Henry Kolker, a well known actor himself, would be directing. Once again, the cinematographer was Harry A. Fischbeck. The May 6, 1921 Variety and May 7, 1921 Moving Picture World noted that Arliss would henceforth release his films through United Artists. The deal was brokered between the studio and Arliss’s producers, Distinctive Productions, Inc., a company that was specifically founded to produce Arliss films. Clearly, Mr. A was avoiding corporate bigwigs in the studios that had marred his dealings with Herbert Brenon.

The May 13, 1921 Wid’s Daily noted that the picture would be shot at the Whitman Bennett studio in Yonkers, NY, and that outdoor location filming was done at the sumptuous 1,000-acre estate of George D. Pratt in Glen Cove, Long Island, NY, according to the June 11, 1921 Wid’s Daily and June 18, 1921 Moving Picture World. It was also noted that through the efforts of George Arliss, Pratt allowed his residence to be filmed in association with the Society for the Relief of Devastated France, which secured famous homes for movie productions to raise funds.

The silent version of DISRAELI used some key members of the 1911 Broadway cast including Florence Arliss as Lady Beaconsfield, Disraeli’s wife, and Margaret Dale as Mrs. Travers, the spy working for Russia. The film premiered at the Mark Strand Theatre in New York City (as did THE DEVIL some nine months earlier) on August 28, 1921, according to the August 27, 1921 Motion Picture News. A general release date of September 3, 1921 was cited in the December 10, 1921 Exhibitors Trade Review. Critical reception was positive, with George Arliss receiving consistent praise for his performance, as noted in the September 3, 1921 Exhibitors Trade Review. Ticket sales reportedly broke a box-office record at the Mark Strand Theatre in Albany, NY, where only $40 was spent on promotions, including simple window displays and “a specially prepared letter” sent to 5,000 Albany residents.

The historical Benjamin Disraeli was also a successful novelist whose writings were brimming with wit. Many of his bon mots were used in the play and film versions while others were invented but were in his distinctive style. Arliss himself was noted for his unique style of delivery and made excellent use of his early experiences as a fledgling playwright. Back in 1910 the first out-of-town tryouts of DISRAELI were dogged by the lack of a powerful climax. Dozens of writers had been called in to create more punch for the finale but nothing worked. Finally, “somebody” – Arliss always denied that the person was himself – came up with a line for DISRAELI that brought the curtain down to thunderous applause. Of course, the line was pure comedy and was repeated in every incarnation of the play thereafter.

Judging the silent DISRAELI today is not possible. It is apparently a “lost” film although the Library of Congress states that a print is held in the Russian state film archive, Gosfilmofond. This writer contacted the archive with an inquiry and was promptly told that it held no material on DISRAELI. There is word that the Belgian Cinémathèque royale de Belgique film archive holds the first four reels of the film (out of seven) but reportedly the material is too fragile to be copied. The George Eastman Museum in Rochester, NY, once held a complete print that it screened at the institution’s 25th anniversary in 1947. Today it reports that only a few fragments remain totaling about one reel.

However, by reading the play script, watching the 1929 film, and listening to the 1938 radio broadcast, we can get a good idea of the silent film’s impact. Among the cast, an unknown Reginald Denny played the nominal hero, Lord Deeford. Within a few years Denny would be starring in a successful series of comedies for Universal, the most memorable of which is SKINNER’S DRESS SUIT (1926). The popular screen actress Louise Huff played the ingenue role of Lady Clarissa, and shortly after retired from the screen. A few years ago, this writer published a photo reconstruction of the 1921 DISRAELI using stills that I had collected over many years. The photos followed the play script fairly well so I was pleased with the way the book turned out. More recently, I returned to the silent DISRAELI in the form of a graphic novel that I also felt turned out reasonably well. Members of Kindle Unlimited can read both books digitally for free.

The Comedies

THE RULING PASSION (1922)

The first outright comedy film made by Mr. A was THE RULING PASSION in 1922. The director was Harmon Weight, who must have worked well with Arliss because they made two more silent films together, the drama THE MAN WHO PLAYED GOD (1922) and his final silent, the comedy $20 A WEEK (1924). The cinematographer once again was Harry A. Fischbeck. The plot was based on a short story, “Idle Hands,” recently published in the Saturday Evening Post by Earl Derr Biggers, a well-known author of the time. Biggers would become more famous over the next few years when he began his series of “Charlie Chan” novels that were later made into a successful and long-running film series.

THE RULING PASSION marked Mr. A’s third film but was the first he had not previously performed on the stage. Arliss plays John Alden, a wealthy automobile manufacturer in this modern dress comedy, who is forced into retirement by his doctor. Bored with being retired, he decides to invest in a gas station using an assumed name and partners with a young man named Bill Merrick. The two are swindled by the seller of the gas station and they strike back by engaging in a price war with the crook who runs a competing gas station. Alden’s wife and daughter know nothing of his secret life until his daughter, Angie, pulls into her father’s gas station. She also meets Bill Merrick and a romance blossoms. Angie agrees to keep her father’s secret under the circumstances.

Alden’s ruse is eventually discovered by his wife but all ends well when the crooked seller begs to buy back his old gas station at a much higher price than what Alden and Merrick paid for it. Merrick goes to see Angie’s father having no idea that he is his partner. Alden feels invigorated by the little adventure and his doctor agrees that he can return to his work.

George Arliss recalled in his memoirs that some location filming was done where an unplanned comedy scene took place. A “make believe” gas station was built there and during a lunch break a driver pulled in thinking the set was a real gas station. He ordered several gallons from the property man who happened to be standing by and he went through the motions of filling up the gas tank. The property man refused payment telling the driver that since it was John D. Rockefeller’s “birthday” all gasoline was free that day. The man drove off oblivious to the prank.

THE RULING PASSION premiered in New York City on January 22, 1922. Among the cast, the role of Angie Alden was played by Doris Kenyon, a popular screen actress who was married to film star Milton Sills. Almost a decade later, Kenyon would play Arliss’s wife, Betsy Hamilton, in the film, ALEXANDER HAMILTON (1931) and Madame de Pompadour in his VOLTAIRE (1933). The reviews of PASSION were uniformly positive and many critics said they enjoyed Mr. A’s refreshing change of pace in a situation comedy.

Unfortunately, THE RULING PASSION is another “lost” film although unsubstantiated claims have been made of its existence. The film did so well that Arliss later decided to remake it in sound in 1931 as THE MILLIONAIRE where it again was well-received. Similar to his silent films, the talkie version became his third film of the sound era and his first comedy of that time.

$20 DOLLARS A WEEK (1924)

Mr. A’s movie box office appeal continued to grow after PASSION, and he felt it was time to turn to a drama. A story about a concert pianist who goes deaf left little room for humor. But THE MAN WHO PLAYED GOD (1922) succeeded as an inspirational story that Arliss remade to equal acclaim ten years later in 1932 for the sound screen. Alas, the silent version is a “lost” film now.

By 1923 Arliss had been appearing in only one play for the previous three seasons, THE GREEN GODDESS. As he prepared to take it to his native London for a run that lasted a full year, he made a film version in the states. He played the wily Rajah of Rukh who toys with his three British visitors who had the bad luck to crash land their plane in his tiny kingdom. Eventually, his guests, two men and a woman, realize the Rajah intends to execute them in revenge for the execution of his three brothers in England. Arliss has many deliciously ironic lines that arouses laughter from audiences but he ultimately shoots one of the male “guests,” tortures the other, and tries to abduct the woman. Therefore, I will resist the temptation to classify THE GREEN GODDESS as a dramatic comedy despite its large comedy content.

Before he left for London, Mr. A arranged to film another comedy called $20 A WEEK, sometimes listed as TWENTY DOLLARS A WEEK. This was based on a short story by Edgar Franklin called “The Adopted Father.” Arliss plays another wealthy businessman, John Reeves, who bets his son, Chester, that they should both find jobs paying $20 a week to see which of them could live on that amount and no more. The role of Chester was played by Ronald Colman shortly before he achieved film stardom in his own right. Colman played the High Priest in the original cast of THE GREEN GODDESS when the play opened late in 1920. Years later in 1947 Colman played the Arliss role of the Rajah in a radio version of GODDESS where he reminisced about his part in the original play.

The March 9, 1924 Film Daily and March 22, 1924 Exhibitors Trade Review reported that Henry M. Hobart of Distinctive Pictures had recently signed an agreement with the Selznick Distributing Corporation for a series of features starring Arliss. The first of these was $20 A WEEK scheduled for release in April. We know that Mr. A opened in London in THE GREEN GODDESS in September 1923. This suggests that $20 A WEEK must have been filmed at some point during the summer of 1923. The July 1924 Motion Picture magazine noted that while Arliss began work on the film in the U.S., his final scenes had to be completed in England due to his play commitment.

The film was directed by Harmon Weight and the cinematographer was Harry A. Fischbeck. It premiered in New York at the Mark Strand Theatre during the week of June 9, 1924, according to Film Daily. The reviews were mixed although Mr. A’s facility with comedy was duly noted by the critics. The June 21, 1924 Moving Picture World complained that the plot relied too heavily on coincidence and improbable characters. A positive review in the May 4, 1924 Film Daily noted a close thematic resemblance between $20 A WEEK and THE RULING PASSION.

Indeed, both stories had the Arliss character hiding his identity and, in WEEK, he disguises himself by wearing glasses and a wig. The Reeves character takes a job as a bookkeeper in a steel plant run by William Hart who, with his sister Muriel, inherited the business from their father. But neither takes an interest in the company and they just live off the income. Reeves learns that the business manager is secretly arranging a takeover of the plant to cut the Harts out of ownership. When Muriel decides to adopt a small boy, her brother William “adopts” Reeves as their “new father.” Chester visits the company and he and Muriel fall in love. Reeves manages to thwart the takeover scheme, save the business, and becomes a partner with the Harts.

Happily, $20 A WEEK survives and has been restored by the Library of Congress and presented at film conferences in recent years. The distribution deal with Selznick quickly came to an end when Lewis J. Selznick, owner of the company, filed for bankruptcy. His son, David O. Selznick, later became a successful film executive and produced many top films such as GONE WITH THE WIND (1939). Despite its convoluted plot, Arliss liked the premise of $20 A WEEK and would rework the vehicle nine years later with much better results. Retitled THE WORKING MAN (1933), the sound version co-starred Bette Davis as the sister and is considered one of the very best of the Arliss films.

When George Arliss returned from his London engagement in late 1924 he quickly became involved with another new play, OLD ENGLISH by John Galsworthy, that occupied him for the next three seasons. He made no further silent films but Hollywood would soon be transitioning to sound films. In July 1928, Mr. A signed a three-film agreement with Warner Bros. to make talkies. He ultimately made ten films for the studio at a substantial increase in compensation each year during that time.

In recent years, a few Arliss sound films have received official studio releases on DVD and in at least one case, in the streaming format. However, this writer is yearning for a video release of the three surviving Arliss silent films. These are the 35mm prints of THE DEVIL and $20 A WEEK at the Library of Congress, and the restored version of THE GREEN GODDESS at the UCLA Film Archive. FINIS.

Copyright 2021 by Robert M. Fells

You must be logged in to post a comment.